Experience teaches you things

It's important to tell your story and to put your stuff out there because you never know how it's going.

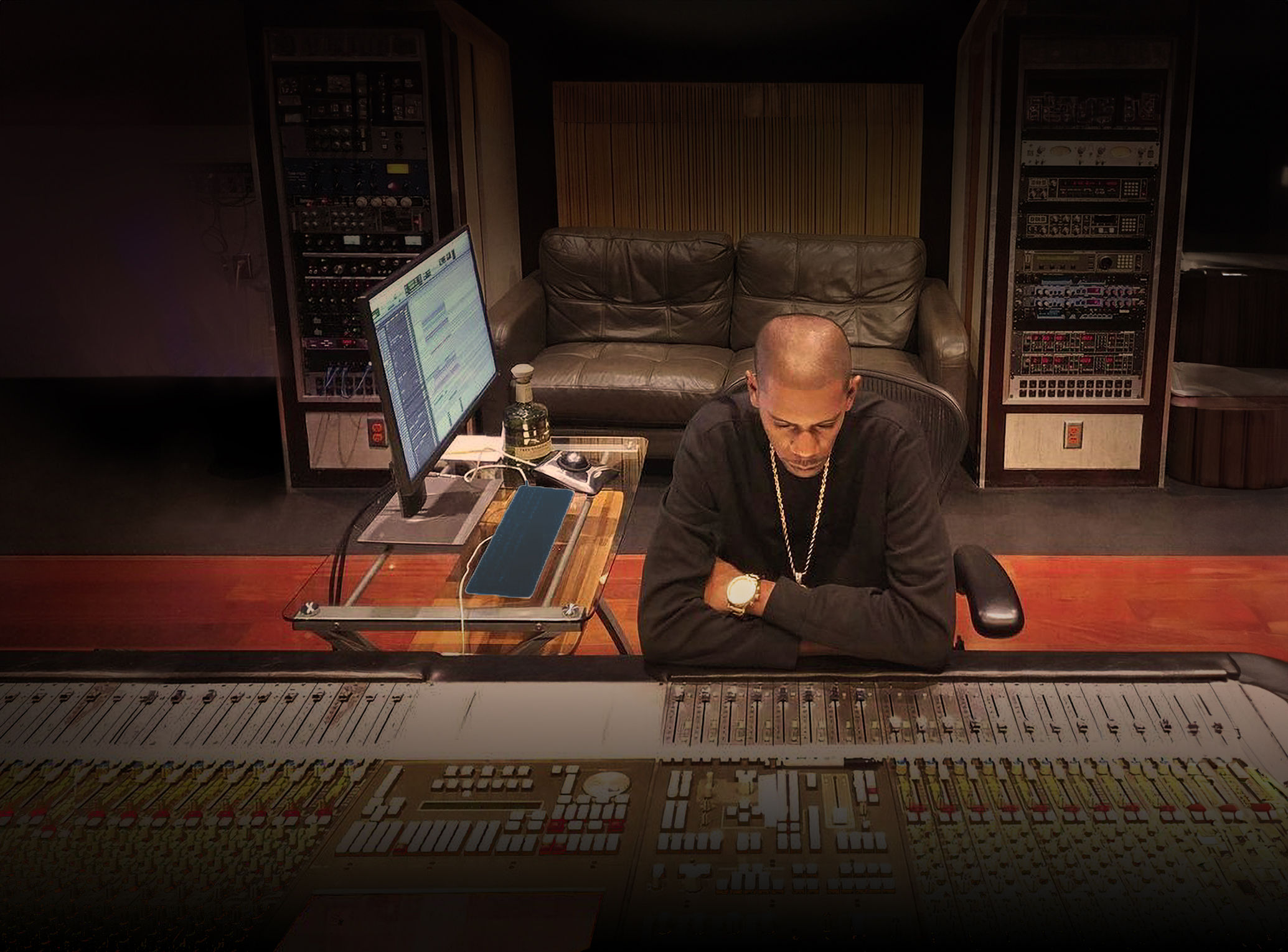

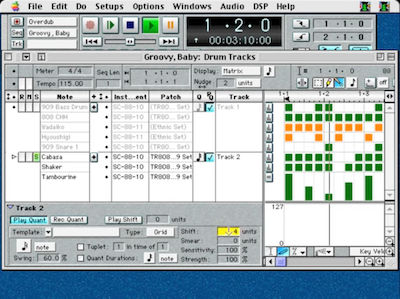

Young Guru

Gimel Androus Keaton, better known as Young Guru, is an American audio engineer, producer, DJ, and record executive who has been working for over two decades with the most influential Hip-Hop artists in the industry and is also Jay-Z’s right hand in studio matters. In 2019, Young Guru won a Grammy Award for Best Urban Contemporary Album for mixing the album Everything Is Love by The Carters.

He recently joined the Roc Nation School of Music, Sports & Entertainment in Brooklyn, New York, as the Director of the Music Technology, Entrepreneurship, & Production program, where he helps to develop the next generation of audio and entertainment professionals. We got the chance to sit down with Young Guru and talk about his musical journey, life, and some plug-ins, and primarily discussed the topic, 'How to put yourself out there.'

Spending time with Young Guru, one starts to understand why his fingerprints are all over so many great records. We're honored to share Guru's story with you.

Where did it all start off for you?

Even before engineering, what got me just deep into it, I mean not just music, but the technical aspect of music, is building sound systems and DJing at parties. So, my earliest thing of like that first initial jump out there is going from my bedroom DJing to actually DJing out for people. That's probably the first time of trying to get, you know, go just to stick yourself out there.

Engineering-wise it was different because, as someone who grew up in Hip-Hop, my first time ever just trying to go to a studio was trying to emulate and produce records that I heard on the radio. And I had no idea how they were doing it. All I had was album covers to look at. Maybe EPMD might have taken a picture with an SP 1200 or something on the back. And you would like, ‘Okay, well, that's what they're using,' you know?

So, at that time, I was constantly reading all those magazines that were readily available and kind of just looking the stuff up. And when you're reading articles, and you don't understand what's going on - this is before me going to engineering school - you kind of don't understand all the concepts, and you start looking those up and figuring things out.

My initial thing was paying for studio time to try to produce. And Hip-Hop back then was sitting at home and going through a bunch of records and kind of constructing this thing in your head. This was me being young, like 14, 15 years old. I saved up some money, found a local studio, and went in there and had no clue of what I was doing. And the engineer that was in there was sort of a rock engineer and didn't really understand like perfectly how to work samplers. Remember, Hip-Hop was new, and this wasn't a common thing for a bunch of people, so the people that had studio setups were kind of from the Rock Domination era of the late 70s and 80s.

That's what really got me into it I had to figure out how not to waste money, and you know, like figure out all this equipment. Then most of my upbringing is me trying to engineer for my own groups of people. Everybody in my neighborhood knew me from DJing, and then we would try to make records, and that was where I initially started. That transferred into the same thing in college. I went to college with the purpose of like I'm going to become a DJ on the scene in Washington DC, and this was in ‘92.

And I’m also with a group of people at Howard University trying to be a Rap crew. So inside of my crew was Tracy Lee, who ended up getting multiple deals, but his biggest deal was with Universal with Mark Pitts, and he had a big hit in ‘97 - The Theme.

So, from ‘92 all the way to this point in ‘99, this is what it was, we were going to a studio right outside of DC, Maryland, and there's a great engineer who's passed away, named Scotty Beats, who ran the studio. He was like the first young black guy that I saw that knew how to work the equipment but also understood the culture of Hip-Hop. In ‘96, I became Nonchalant’s Tour DJ.

We went on a Fugees tour, and right before that tour, I was like, all right, I'm going to Engineering School at Omega Studios. As strong as I was with beat machines, and how they worked, and Synth and MIDI, and all those things, I had never done a Rock Session, I had never done a Jazz Session, I had never done a Gospel Session. I wanted to learn all the things I didn't know, and it was just a great experience, a great school, very personal.

Learn the priority of order of what you should be doing.

How do you apply music theory into practice in a real studio environment?

You have the textbook knowledge, but then to be able to apply it in a session, and when someone's quickly asking for something or you start to realize these things that I've concentrated on may have to wait until after the client leaves because I need to facilitate speed right now. You learn to prioritize a couple of things because I could sit there forever, for two hours on just the snare, but it's just the client who doesn't want to sit there. Learn the priority of order of what you should be doing.

Especially now, because people are in their bedrooms from beginning to end. It's a tough sort of thing because, with the access that everyone has, it's still a learning curve of how to make good audio. You may have never heard of good audio, you may have never heard these microphones that were designed specifically for audio, and you may not understand the science of treating your room. In a studio you're not only keeping sound out, but you're also keeping sound in. I think the beautiful thing is that now we have all these great tools, but it's also a case in point where some of the apprenticeships of being in a room and actually hearing well-done vocals or well-done drums or a well-done bass or distortion the right way, you don't necessarily have those experiences outside of your bedroom. That's sort of the toss-up of the thing of stepping out fresh.

I think the biggest thing, too, is that the issue for a lot of the students and a lot of the people that I talk to is pricing. They don't know how to price, you know when they first step out, and they're like, well, I don't have this rack of awards, so how do I price? They also don't fully understand deliverables, and when I say deliverables meaning, there's a bunch of people who just make a song and post it. But they haven't worked with the company enough to know, oh, I have to do the instrumental, the acapella, what happens if this person wants to perform, then there needs to be a TV track. And I'm talking about Hip-Hop and R&B. The worst thing is if this artist you're working with, and you created a great song, wants to put it in a movie. And you didn't do all the stems because the movie house wants to have stems to be able to edit. They don't know all those steps of deliverables.

That helps you in terms of pricing, in terms of explaining why you're pricing the way you are. Being able to say, you know I charge this much if I'm doing a two-track. If I'm doing a four-track, I charge this much, and so on. And those are the questions that people have to judge and see what the steps are.

What makes a successful engineer?

A lot of engineers who are becoming successful, again, at least in the Hip-Hop and R&B world, are those who are kind of latching on to an artist. And I’m proud to kind of say that a lot of people are like, ‘Hey Guru, I look towards your career as that,' and I'm like, well, you know that's great, but we just have to see where it goes. So, they'll look at me, they'll look at Ali, they'll look at 40.

I can go down the line of these big artists that have one particular engineer that they work with. Migos has one engineer that knows their sound, DaBaby has one engineer that knows his sound, and that whole thing has become a way of people getting in, but it also makes people think like, if I'm not doing that, what do I do? But there's so much work out here that can be crowdsourced.

And I guess that's the biggest question when you're putting yourself out there, beyond, am I good enough, do I know enough, is my sound developed enough? The natural questions that engineers ask themselves in trying to figure out mixes.

The best advice I can give is just to learn your room, regardless of if it's treated or not. Learn your sound.

It's like these NS10s. Everybody knows that they're not the greatest built speakers, but why they're so loved is because they give you truth. If I can make it sound good on those, it's going to sound good on any. And you don't have to have the million-dollar place, no. But you do have to know your room and learn your room.

One of my biggest things over the past two years was that, obviously, through COVID, I was trapped in an apartment that I had just moved into in L.A. Because I was out here working and all of my stuff was on the East Coast. But I'm in L.A., and it's COVID, and I'm just like, okay, I have to get an apartment, I can't live in hotels anymore. So I quickly had to learn this space. And I also learned that I like sitting this close inside to the speakers to create that triangle. Because my whole life, I’ve been so used to having a full SSL board between the speakers and me. It's like, oh, I've never done it this way to where I’m literally sitting in the sound now. And I get it why people like this versus like there is a four, and five-foot difference when I'm sitting behind an SSL or any major board in the studio. You start just to learn those things, and those things help you. And again, this is really back to that question of how do I put myself out there, how do I start? When am I ready to start? I say always look locally to work with some people when you're initially trying to see what you can do. There are things you can do.

Charity is the biggest way to money, you know? KRS-One once told me that when he was at my house one time. He's like, you got to give away some stuff, and then see what comes back. So, you may have to step to someone and say, hey, if you guys are working, can I at least give this a shot? Can I try?

One of the other things that I think is really good in this time period is that the stems from so many classic songs appear online, right? And not to say you're going to take those songs, and a lot of DJs remix them unallowed, or do whatever. But for mixers and for engineers, it's good just to download the Nirvana stems and see if you can make it sound like that. Or if you can, you take it somewhere else, so what would you have done with that, or understanding how many times guitars were mic'd. When I got the Nirvana sessions, I was like, okay, this is why three people can sound so big, because of the way that its mic'd. It's mic’d three and four times on every instrument and on the drums. And each guitar has three different versions that he used to mix.

So you start to learn those things or just practice, you know? I can speak on New York City culture throughout the 90s and the 2000s. Every engineer that worked at Hit Factory, Sony, Quad, in any of those studios, when the client left, you have the whole closet of reels that are sitting there, and you can just take a reel and just put it up and like practice on people's songs. And a lot of engineers got really good. You know they didn't make a copy because that was just such a no-no back then, but it was like, ‘I have this reel of this hit record' and can go practice.

When you're at AES, when you're at NAMM, it's impossible for you in that room to really hear what this mic is gonna sound like. Or setting up five different microphones that you don't own, and having someone play and you get to just sit there for an hour and see what each different one sounds like. That part is missing.

I think those things help people to get further faster if they realize that those things are missing, and these are not things that you can get on YouTube. There's a lot you can get on YouTube, and a lot of instructions, and the way that people work and see those things.

My school was very good at explaining concepts more than application - meaning if I know what a compressor is and what it does, and what all the different forms of it, then I don't walk up to a new compressor asking what these buttons do. I walk up to a new compressor going, ‘Where's the attack, where's the release, does it have an attacker release, is this the screws, it's an Opto, how does this work?’ I'm looking at it for those sorts of things versus just being, ‘Okay, well, what is this?’

You have the concept, and then now it's much easier for application once you understand the concept because otherwise, you're going to be chasing the latest feature on a plugin forever. I tell students all the time they'll learn these concepts. And everything doesn't need to be side-chained, or everything doesn't have to have harmonic distortion, or else the whole thing sounds muddy.

And I see a lot of Engineers who don't commit and spend a lot of time later trying to make a choice. And it's like you should have made the choice then on that day, which helps with getting out there faster.

If you are learning to commit helps a lot. If you learn to commit to things.

If someone plays guitar and you recorded it dry, and then you're just sitting there for two hours flipping through guitar rig or whatever your favorite thing is, and it's like, you know, just come on, like ‘Get the vibe of when the person's playing it,’ pick a sound and go with it.

Yes, there's an ability you record the dry one and the one you process at the same time, and then if you don't like it, then go back and change it. But you have a vibe set already on that day that person was doing it. I'm old enough to remember when word processors first came out. I went to High- School and, at the beginning of college, typing papers. And then when the word processors came out, it was like people were handing in papers where all these different fonts and things were underlined and in different colors. It looked like retarded.

But you don't need to use every single plugin in every single thing. Some things can be underlined, some things can be italicized, but learn taste. And the whole idea is to present your paper in the correct way, not to utilize all these functions because you're just hyped. Because we have a word processor now, and if you are making a mistake, you can go back. You know, those things I say, help people.

With so much information and platforms, one or another can get confused and overwhelmed. And when there’s a different approach for beat making vs. song creation, what advice would you give?

You know that we've gotten to this point now, and don't get me wrong, if that's what you're going for like there is a complete beat culture out here now, you know where it's like just the beat. I have producers sending me stuff, and I simply say to them, ‘It sounds like you arranged this for a beat battle and not for someone to create a song over.’ There's a complete difference, so that is a big thing too.

You have to have the ability to sort of understand what you're doing with it and what's your purpose. So if your purpose is to create beats that will be on the Lo-Fi YouTube page because that gets so many hits, then great, go do that. But if you are trying to create songs and win Grammys, then there's a whole other aspect of creation and getting it done. That's more about how good the song is, and that part gets lost so much on people. They watch these things, and they're trying to perfect certain things.

One, you have to be careful. There are no rules in this. So everything is someone's opinion. You just trust that they're experienced. Experience teaches you things. But what I'm saying is you have to be careful that the thing that they're telling you, just because they're a respected engineer, applies to what you're doing. So if you're watching someone working in a completely different genre than you, who doesn't deal with any of the things you deal with, some of their information may be correct in what they do but not correct for you. So you have to be careful of that part on YouTube.

Then you also have to be careful that there's a bunch of people out there giving information who have failed at the thing that they're telling you how to do. It's like, who are you getting this info from? Because a lot of times, people are telling you how to do things that they've never done themselves. They have all these things on, this is how you get clients, and they have never done it. Even worse is, they may have done it 20 years ago, which may not apply to the way that it works now, you know.

I love that part about teaching that keeps me in tune with a 16-year-old mind, 18-year-old mind, and a 23-year-old mind of engineers, and where they're going in today's space.

And they push me constantly. I constantly change, or I look at other engineers that I respect, and you know, during COVID, I pushed myself to get outside of what I normally do for my mix, and it sped my workflow up and made me think.

Even still, I'm learning new things and just applying them. I think that's the part of being careful of where you get the information from, but yet how am I going to apply this? And then being able to understand it to the point where you can do something that it wasn't meant to do, or that like stretching it outside of its capabilities. That's what creates new and unique sounds and leads people to different places. If everybody has the same preset sounds, then it's going to kind of sound the same.

It's like, what do you bring that's different? What is your thing?

I personally like Timbaland’s Beatclub. The community is very helpful and very like-minded. I can communicate with other users on Discord about beat-making and get answers very easily. It’s fun.

I absolutely love those things online, the things that are less fluff, and fewer people just talking, and the things that get directly to what I want to do, right? I'll give you a prime example - I don't know for how many years I have loved Ableton, right? Of course, most of my mixing work is in Pro Tools because those sessions are coming in Pro Tools, but production-wise I love Ableton, and I've been in it for a while, and I love it.

So the majority of producers in the Soul Council are the producers that are underneath 9th Wonder, and our label is Jamla. And we have other conglomerate producers who use Machine. And one of the things in challenging myself and being that guy that loves to know how to do everything, I went, and they had an extra Machine laying around, and I was like, ‘Oh, you got an extra Machine. Great I take it.” And I'm learning, and I can't figure out how to do certain things. I love to go to YouTube, and there's a two-minute clip that says okay, ‘How do I name a group in Machine,’ plus, the guy just goes, ‘Okay, this is how you do it versus me having to sift through a 20-minutes video. And he's kind of saying it real quick in 3 minutes. And I like those sorts of videos a little bit better. Those, for me, are the good ones. And when I leave a comment, people are like, ‘Guru, you're on here learning?’ I'm like yeah, I don't know how to work Machine, and there's a kid who's been using it for eight years, so I'm looking up how to work this thing. Or Fruity Loops. I didn't know how to really work Fruity Loops. And I started to see a lot of younger producers were using Fruity Loops.

In our time, we had a distinct sound with the S950 and with the MPC3000, and the SP-1200.

I could tell what beat machines meant, so I could start to hear the full loop effect on many people's beats. And I was like, ‘Okay, well, what is? And I went online, not that I'm super proficient in Fruity Loops, but at least if I get a session and it got clicks and pops and some things I want to fix at the root of it, I can at least do that in Fruity Loops.

And so that's my go-to, but I like those videos that get directly to the point without someone's opinion getting thrown in the middle of it. I think those are super effective. You also have to remember that there's an audience being served who may not necessarily be Audio Engineers at the core, right?And the same example you gave, I did that same thing with Adobe Premiere. Do I want to be a Video Director? No, but my artist wanted to make a video, and I have a camera, so I went outside and filmed. Then I came back in, and I went on YouTube and did the same sort of thing, learning Adobe Premiere in 30 Minutes. I sat there, I took notes, you know, I learned how to edit, I learned how to cut. If there's something that wasn't covered there, I literally type in ‘How do I slow down video in Adobe Premiere, and then a bunch of things will show me exactly.

And I'm saying that from a standpoint of there's a bunch of people now who may be doing audio stuff like that in reverse, meaning there are video directors who actually want good audio, and they're learning. So they jump online just to see how to do this in Pro Tools or Ableton or whatever format.

So there are all those great tips and tricks that are online. You just have to be really careful about where you're getting that information from because some people just learned from someone who didn't know, and then they're repeating wrong information.

It's pointless to have these debates about do you EQ first or compress. There's never a situation where one dominates the other - you do whatever you want. There are times when the signal is super muddy and nasty, and it's a vocal that was too much proximity affecting. I got to take all that out before I compress it, or the reverse, it's thin, and I want to compress it first and give it somebody before there's plenty of time. So those debates are the type of things that I'm talking about.

I don't like having to stop and think in the middle of a mix to make a challenge-response. It's the most annoying thing. I just want to flow.

The evolution of digital audio is radical.

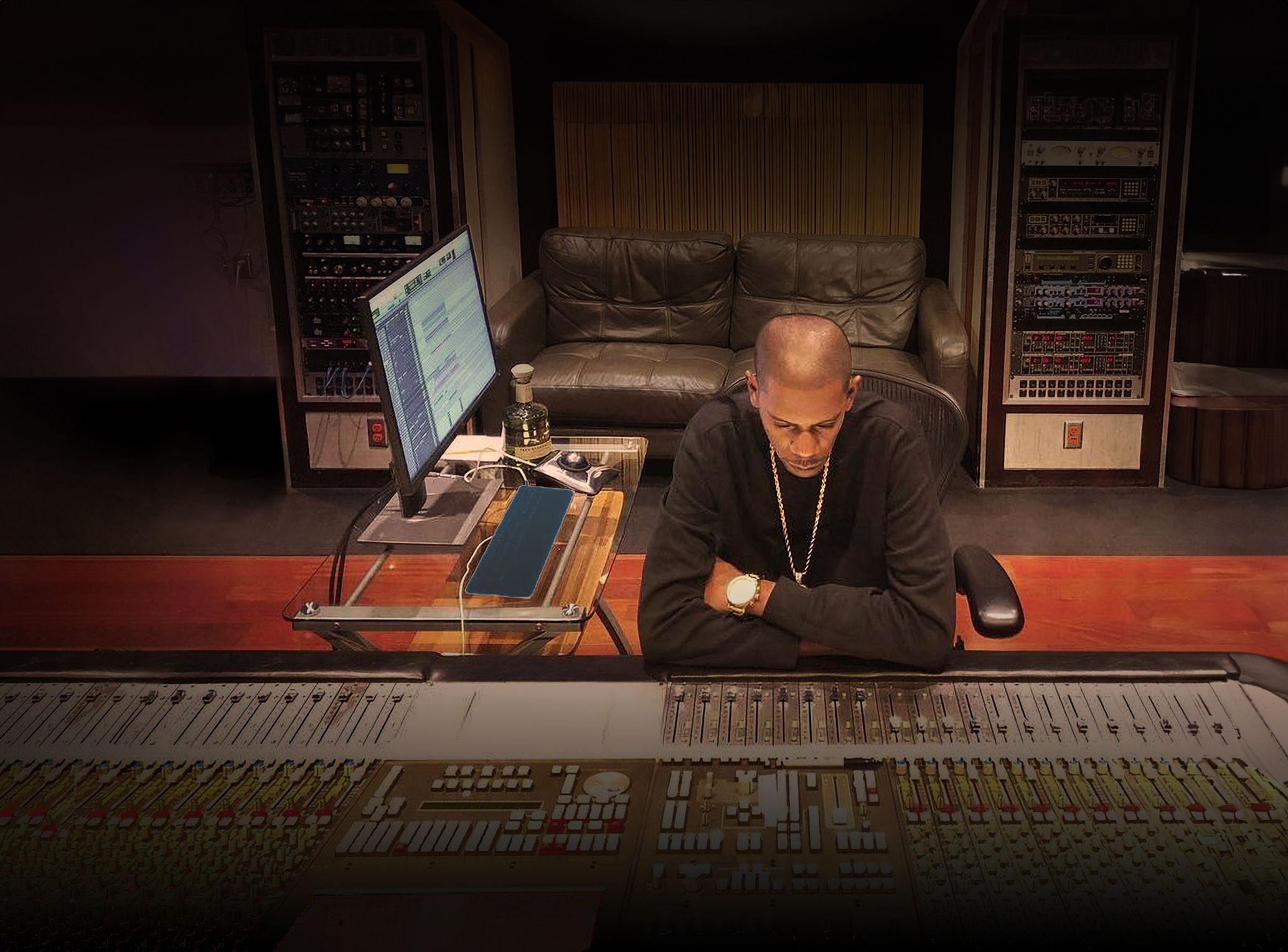

I went to Engineering School in 1996. Back then, digitally, there was no Pro Tools! So we learned Sonic Solutions, which was ‘DAW class,’ because Pro Tools had been invented, but it hadn't become popular yet to that point. Back then, it was the closest thing to that. Or the thing that I knew was Opcode Studio Vision Pro. So Opcode was great. I'm sad it's not around anymore. Opcode was just known for MIDI, like the eight in eight out MIDI converter thing you would use, and then Opcode transferred a lot of the MIDI stuff into Sonic Solutions.

Opcode Studio Vision Pro 4.0 tour (part 1 of 2)

Source: YouTube/ Deep Signal Studios

And then they came out with this thing called Sonic Solutions Pro, which was the first time that I saw a MIDI arrangement and an actual audio file on the computer. Like ‘Oh Wow,’ the audio files in the computer - that was a mind-blowing concept. I mean to watch someone chop it and move it, and I only need eight bars of this thing, and then I can repeat like, “What, we don’t have to record for six minutes?”.

Those sort of things were my initial introduction to digital audio, and I think that sort of thing has helped me over the years because I've just grown up with it like I've grown with these companies and seen what they do. How much better have the tools gotten, and how much faster. I literally was over at a friend's studio and a famous DJ named Kay Slay, who just passed away, I went over to his studio because he has all of the mixtapes and not only Kay Slay’s but just like everything.

So I plugged in my four terabytes solid state drive into his computer, and we transferred 300 gigs in like seven minutes. Back in the day, thinking about transferring 300 gigs? Like Just Blaze and I were hyped when we got an 18 gig drive, we're like, ‘We'll never need another drive ever again.' This is in ‘99. You know, we probably paid a couple of hundred dollars for like 18 gigs. Where we've come is just incredible.

I have the whole history of every Pro Tools session that I've ever done on one small four-terabyte drive. There are bonuses to where we are. There are also drawbacks, you know.

I was telling you I've been in my apartment for the two years, with quarantine, and then I had an album for Reuben Vincent, who’s my artist on Jamla.

So I did my setup of just getting everything together, kinda pre-mixing everything together like vocals and things like that. It's easy for me to do it here to level them out. I do a lot of clip gaining before I do compression, things that are like where the vocals pop up more than anything.

And I may set a threshold level just for these, maybe five times in a verse. I could even clip gain them down and then compress for more for texture and less for control. I do all that stuff here. But meaning to say I stepped into a studio, and one of the major problems is it took even with sending a plug-in list early. It took me probably about three or four hours to get their computer up and running to have the plugins that I need to bring my mixes up. And it's not even all my plugins - it's just like, ‘Okay, these are the things that I need. Some of them are on my iLok keys. Some of them you have to like disable on your regular computer to be able to use on another computer.

There's no standard whereas, back in the day, it was like ‘Do you have a Tape Machine?’ and ‘What level is it at? That's all they needed to know. It's just like this. Is it plus six, plus three, or plus nine? That's all we needed to know, and then it's just like, 'Okay, the Tape Machine is ready.' You cleaned it, put your tape up, and at the most, you may have to be like, ‘Oh well, they don't have enough 1176s, or they have the blue one, and I use the black one', whatever. There were only like 50 different pieces, probably. Sometimes people had boutique things, but you had to bring that yourself. If I have this one snare that I know no one has if I have this one guitar pedal that I know I'm gonna bring versus nowadays, it takes so long.

It's almost to the point where I'm like, ‘I might as well just walk in with my desktop and just plug it into your Pro Tools system,’ and it would be way faster than setting up your computer to have all the plugins that I have because I have all of them. So it's just then you have to pick and choose about what things you're going to do, and I don't just like work, I don't like having to stop and think in the middle of a mix to make a challenge-response. It's the most annoying thing. I just want to flow. Because once everything's correct, I can knock out two or three mixes in a day versus me sitting there technically. I don't mind Tech-ing if that's what I'm doing for the day. I'm gonna get my computer up to speed. I'm gonna do all the updates versus when I'm trying just to flow and mix.

So that's a drawback of how we work nowadays. It's almost like that's an extra step where it's just annoying. And this is for someone who doesn't want to do cracks. I don't want to go through that, I want to pay for everything. I want to make sure that the plug-in companies that are developing these things get their money. And I understand the challenge of the money, and how much R&D costs, and that you have to pay staff, some of the people have to do health care, and you have to keep lights on. And all these other things as small companies.

So it's really not advantageous for you as a user to try not to have plug-in companies make money because the more money they make, the better services they can give to you. People don't understand how much goes into that as a small company. You open a company, you want to make plugins, you make the plugin, and then you're spending like 40, 50 percent of your time in service. People calling and like don't know what they're doing, and it's mainly, probably their fault. But then you have to go through this whole thing are you on a Mac, are you on a PC? It's like hiring a whole person now because this comes with making plug-ins.

So again, I understand that whole process where everyone may not think about it. And they may think that every plug-in company is as big as Waves. No, some companies are five people or ten people, and they make great stuff. All of that comes into play in today's modern society of mixing and having to take into account. All these things when you simply say, I want to go to a professional studio and mix this record.

As a small boutique plug-in company, we carefully allocate resources to tasks and projects.

It’s a great thing, and I don't want to say it as if it's bad. It's just the reality of where we are. But it's also a great thing of before that was sort of impossible, you know? To do a physical thing and to be able to get it across the world, and to be able to do service, so much money had to go into it.

So the same thing, if I wanted to create a film in 1989, the process of doing that was damn near impossible. To create a feature-length film, we have these famous stories of just directors who like maxed out credit cards just to make a low-budget film because that was their dream, whereas now you can just choose a Sony and you're equipped. You can take all the time you need, you can go do shots whenever you want, even if it rains on that day.Versus the people that were trying to do it for real, go to B&H. You rent a package, you got to get your whole music video done on those two days because you rented this equipment from B&H. Whether it rains, you have to get it done. Imagine that with a major motion picture, and now you can do it.

There are a million people who are paid as a photographer, who's never touched film, who's never had to develop film, who don't understand the cost of what it was even to print my stuff to make a book, to take to a newspaper, to take to a magazine, even to have a portfolio to show. Those things digital just helped us so much. But again, the drawback is that in one apprenticeship period, those hurdles made you serious. Am I really into the music, am I going to sit here in front of this pawnshop every day, save up money, talk to the pawn guy, like to put the beat machine in the back so that no one buys it, and hopefully by the time that I can save up the money to go get it so that when I get it, I value this thing, I master it, you know, this is the only thing I have.

So you dive deep into it, whereas today, I feel like people are getting a plug-in and don't master it. They just use presets, you know, and it's like no dive in. Like one Saturday when you're not mixing, go back, and you'd be surprised if you would go back and watch all of the original basics, like the MV2 from Waves, you know? And I hate to shout out other companies, but just something that has been there forever. I never used it, and then I saw someone use it, and I was just like, ‘Why have I never used this, it's so good.’ And I just went back, and it's like a basic, it comes in every package, and it's been there for years. And it's just like because you're always looking at this new thing, that sparkles thing. No! The workhorses. Go ahead and learn those.

I wonder if anyone reads the manual.

People were like, ‘Oh, reading the manual is going to trap me in the way they want.’ I do know where it came from, but I just disagree with it. I’m just going to discover how to do this. And yes, of course, get the thing, play around with it, do it for a week, and see what you can figure out, see what you can't figure out, but then eventually sit down and just read the map! Somebody took time to write this manual. I like reading the manual to figure out exactly what was in that person's head or if there are certain things that I know are left out on purpose because people have proprietary information.

We try to make people aware and fully understand what our plugins are, what they were designed for, and their capabilities. We don't do emulations.

Let me say this very carefully. There are a lot of plug-ins that go after older-sounding equipment. And the whole advertisement, the whole debate becomes does this emulation of an LA-2A sound like a real LA-2A, and I’m like, there’s no two LA-2A sound exactly the same. Which one are you comparing it to? You know, like, if you have one that's been sitting there for however many years it's never been recapped or anything, it's gonna have a certain sound to it. You recap it, you're putting different pieces in it because you can't get the same exact capacitors that came with it, so it's going to sound a little different. What are you you're comparing, apples and oranges?

You should be looking at plug-ins like ‘Does this compress well?’ Not does it sound like this thing, and I understand. It's like you're putting someone in a mental space. If you're going for the sound of what an Opto compressor does, then yes, this is one of the examples of that, and we as human beings do picture association. I wonder if people could mix if it were just like you took the pictures away, and it was just sliders or knobs, or it didn't look like the thing you're trying to, you know.

Step inside the impressive studio of producer No I.D. for a series with Young Guru!

Those are the mistakes that I think people make in arguing about whether this sounds like this or that. Don't argue about it, go compress - does that one compress the way you want, no, then move on to this one, and does that one do - okay, then stop, that's it. Then move on to the next sound, don't argue about this 1176 sound like the real thing. That's not the point. The point is that we have tools, and when we went into digital, we realized that we lost something, right?

There was a heft or a weight in sending each individual sound. You have to think about what the signal flow was if I set up drums out here, and then I have, let's say, eight microphones on that drum kit. I've doubled mic the kick, I've doubled mic the snare, I got two overheads, I got toms, whatever it is, and each of those is going through a preamp right through all the circuits on the board, then hitting Tape, right? Then when I’m going to mix that song, I’m now playing the tape again, and that signals hitting preamps again and then coming through all the stuff.

Like these are all the stages that gave it all of that warmth. So we started creating plug-ins to try to put that back into the music. And I get why people do it, but I think because of the fact that we did that, there become these trends of like the plug-in face looks old, so it's supposed to sound old. And just because putting dirt in the actual UI, it doesn't mean that the sound of it is gonna be dirty.

All these little frivolous things that I think people sort of concentrate on have nothing to do with what you're actually getting from the DAW, you know? You can give me basic plugins for anything, and I’ll make it work. My analogy, yes, I would love to be an auto-mechanic in a garage that has all the latest power tools, that has a thing that lifts the car, that you can hold the wheel. Yes, I want all the tools, and I don't want to sit under a car with one wrench. Can I do it? Yes, when I know what I'm doing. So that should be the mentality. What are the things that help that person that works in the garage is faster and then can do more work, and do quality work, because they have all the tools, but they don't need to pull out every tool, just to do an oil change, you know? That’s the point with plugins.

I'm an engineer at heart. I just love systems and how things work.

What keeps you motivated? What inspires you?

I’m kind of always motivated to work, and to mix, and to do what I do, but life in general. There's a lot of stuff that I do. Photography was me trying to exercise a different sense, meaning that if everything in my life is auditory, and just listening and sound, and all of that for so long, I want to creatively have a discipline now that has to do with sight and light. It's just like when we're in music, we're writing with sound, and when it's in photography, I'm writing with light.

It's just a different discipline and a different way of looking. And it's also this kind of way that we have that I had to get over as an engineer. Once you get into engineering, it's hard for you just to sit back and listen to music, just from this pure enjoyment standpoint. Because you're always thinking in this engineering mode, right? I've trained myself to get back to being the consumer of like, stop thinking about how loud the snare is, where the vocal sit, or what's that reverb. Just enjoy the song. Because I’d be in the club, literally like why the person has a snare like, you know? You're supposed to be like getting drunk, and if you don't, you're gonna miss what the audience is looking for. As the person that's producing something, you have to think about your audience at all times because the audience doesn't care what the plugins are. They don't care what board, format, or DAW you use. They only care about two speakers. I was saying I take on photography and things like that to exercise different senses.

And I read a lot. I'm just an engineer at heart. So when I was young, engineering, not just musical engineering, but engineering in general and the art of engineering, design, and building something. But there's a difference between different forms of engineering that's interesting to me that I fell into. So I was in this program called FAME. My mom was just really good at finding programs in the hood that would help. And it was called Forum to Advance Minorities in Engineering, and they would just introduce you to everything from civil engineering to just every form of engineering possible. And this was very early when computer engineering was very foreign to people. But I just love systems and how things work, and I would take apart bikes, and I would fix people's VCRs, and I would learn all this other stuff because I like the systems.

But also with, let’s say, architecture, where some art forms are abstract, and you can just do whatever you want. No one can really say if it's good or bad. It's just your taste versus architecture. If I’m making this interesting building, there are still things that have to go. People have to be able to walk on these floors without them falling off, you have to be able to have a certain amount of wind hit the building without it toppling over. The physical structure has to work, not just be beautiful. An architect is considering where to put the windows and from where the light is coming in. If you've ever seen the buildings at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) that are like crooked sort of design to it, that still has to work physically. It can't fall over, so those things are super interesting to me - the combination of art and functionality. It has to function and still go into this thing where it's beautiful. So I think those things help me in terms of when I look at other things. Or things I'm just interested in, and by no means am I trying to become an architect, right?

I was good at my engineering classes at drawing, and before we had CAD systems of computer automated design, we'd sit, and we'd have a little desk where you're just drawing all of your designs as an engineer. I think all those things where I study just life and things outside of music, to have things to write about or things to know where everyone is. And studying why people create the music that they create, meaning background stories of artists, the producers, the engineers, and the labels. Just everybody that was involved in what their mind state was.

I'm not just looking at Thriller as Thriller. I’m looking at Quincy Jones, I'm looking at Rod Temperton, and I’m looking at Bruce Sweden. I’m looking at who are all these people and where they were in their life when they converged on this one thing that became so monumental. And look what happens to your career when you don't include these people, you know what I'm saying? So it's just like magic that came with those four or five people. I’m not saying later with Teddy Riley, Michael Jackson’s albums weren't great produced, but the magic happened with those people.

Another thing, look at Motown. When it moved from Detroit to California, it fell off. Why? What was it about that room? It might even just be the room. It might have been that the musicians could go to a bar down the street that they're familiar with and get drinks at a discount because they're only getting paid 300 dollars a week, and that bar’s services, all these factors that you may not factor in. When you remove the Funk Brothers from that environment, in that equation, the music is not the same! You know, studying those background stories and what got people to a certain place is just as important as studying The Beatles’ Red Book of ‘Okay, these are all the microphones that they were using.’ You're not creating The Beatles’ music, and you're not doing it at Abbey Road.

You got to know the other part of it more than just the technical. Again, it's hard to say that because I assume that's just like the bottom line. The bread and butter of it is you understand mics, and you understand mic placement, and yes, you want to see how they got that sound, but even more important is the what and the why of the situation. What was going on in their life that everybody was in that position, and why did they choose certain things? That is the part. Those things inspire me to go in and okay - let me try to make the best music that I can, because now if they could do that with the little bit of stuff that they had, I'm supposed to be able to do miraculous things with all I have. I have every studio on my computer that ever existed. There's no way that you can have more equipment physically in the studio than what I have on my laptop.

It's important to tell your story and to put your stuff out there because you never know how it's going. And that's art.

I love researching music history and the people behind it, especially via docs.

I love docs because there are so many things that you may not have been able to research or just weren't described. One of the famous things is like us growing up and loving A Tribe Called Quest and wanting to know who produced what because it just says produced by A Tribe Called Quest. Then you're like, 'Okay, Q-Tip did the beat, who found the sample, who did the drums, Ali plays a bunch of live instruments, so what bass lines. So when you get a doc that explains some things, you're like, ‘Oh, okay, now I at least have a little bit of a better picture of what was going on at that given time.’

Stories like J Dilla and his mentor who showed him the MPC.

Amp Fiddler. That's a perfect example of us as Hip-Hoppers. One of the things we do is through shout-outs on records. Or we say, you know there will be these characters who are real people, not made-up characters, but their name just got shouted out on a record because they were cool with the artist, but you didn't know who they were. So Tribe, for plenty of times, said Amp Fiddler’s name on records, so we knew of that person. Then you kind of figure out from where certain people came, like Dilla in his introduction to Q-tip, came through Amp. Because if Amp is messing with Dilla, then he's like gonna play some stuff. Now you realize that this dude's a genius, then you know he has great material, you play it for Tip, and then Tip meets him, and then that's how Questlove finds out about Dilla, and that's how Busta Rhymes finds out about Dilla like you see the tree. But then, it's really just friends that are all together and just excited about music. This guy's really one of the greatest ever.

I heard about Slum Village when my assistant Kamel who passed away, lived on Church Avenue in Brooklyn, and I lived in Jersey. So sometimes, when I’m in New York, and I have this session ended, but the next one starts in two hours, I would just run to his house and take a shower. Because we've been there for three days, and I haven't left, I go take a shower at his house on Church Ave in Brooklyn instead of going all the way back to Jersey. So I was in his house taking a shower, and his roommate was playing this cassette, and I was just like, what is this? I was really like, what the F@<% is this? It sounds like Tribe, but it's better, you know, like sort of thing, and that was my introduction to it.Then obviously, I’m aware of it, and at that time, I wanted to know if it was like really real. Because sometimes you find out, ‘Oh, it's a group of people, ‘Oh, this guy's taking this other guy who's in the basement his name, and I want to see if it's real.

Then Slum Village 2 comes out, and that's the one that was an official release on a CD, and I bought that in Amoeba in L.A. on tour, and then I just went crazy, and I was just like, ‘Who is this guy?’, this is the best sounding thing I've heard in so long. It really made me fall in love with Hip-Hop again.

Slum Village – Fantastic, Vol. 2

Source: Discogs

https://www.discogs.com/master/50736-Slum-Village-Fantastic-Vol-2

So then Jay's cousin Bee-High was helping him in New York, not managing him, but he was helping him, trying to sell beats, trying to get stuff out there. I don't know exactly what their business was, but I figured that out, so I went to Bee-High, and I was like, ‘Yo, just get me a session with him. I'll do it for free. I just want to sit in with him. And then he got it for me.

So the day that I sat with Dilla, it was just me, him, an MPC3000, records, and a lot of weed. And that's just like, I got to see his process and work with him, and understood what he was doing. And he's not the most talkative person, but he's just okay, we're just passing back and forth to each other, and I'm watching what he's doing and learning. And then I was like, ‘Oh, this guy's really that good. He's the best I've ever seen at beat-making.’ And having his own style and the idea that now I'm one of these people that I don't get upset when the masses of people gravitate towards this underground thing that I think is so good because I want my underground things to be really big - meaning there are underground heads who like a certain thing. Then once the majority of people start liking that thing, to them, it's not underground anymore, and they're like ‘Oh well Little Susie from Idaho likes that, I can't like the same thing she likes, I'm an underground. I gotta like this next thing.’

And they kind of leave those artists, and I was like, wasn't the purpose for them to become big, to become popular? Like I could understand if they became commercial and changed their sound, but like Dilla didn't do that, it just became a generation of people after his death that started wearing these ‘Dilla changed my Life T-shirts’, and all this other stuff.

And I'm like, ‘You know it's weird for me because Dilla changed so much for us.’ That we're getting the tapes, he would use to call them treats, and he would pass them out to artists. Like do specific beat tapes back when you couldn't burn a CD, he would put it on cassette and give Busta a beat tape, he would give Talib a beat tape, he would give Common and a beat tape.

You know all these people he was trying to sell music to, we would hear those tapes and just go crazy like way before the internet. It's weird to me that a whole genre of music has been created based on just his 2005 work. That's his most popular work. Everybody just gravitates towards that because that was the first thing kind of uploaded online, and y'all realize that that's like a three-month period for Dilla.

The thing that you are copying, that he has created, this new genre that you all choose, to call whatever, or this Low-fi, or whatever. That's him for three months. Every three months, he changed. He went through the breakbeat period, he went through the solo drum period, he went through the synth period, he went through the ‘I'm doing my West Coast period,’ he was even making Trap Music, back then before it was popular. He was morphing. No beat tape sounds the same, so it's just weird to me that people just pick that era, and they say, ‘Okay, this is now a new genre,’ and it's interesting how these things now affect the next generation and what they know.

So it's important, again, to tell your story and to put your stuff out there because you never know how it's going. And that's art.

Like people that were making records in the 60s and 70s did not know that we were going to sit here, like that part of the record and just sample those drums, and sample this baseline. They weren't thinking in that manner when they were making breakdowns of the song, they were just making them, and they had no idea what was coming. You don't know how people are going to use whatever you do, and a new generation is going always to be different and evolve and try to do a new thing.

So it's just interesting. It's not a complaint. It's just a weird like sort of interesting thing that I've noticed, and I want new generations to do whatever they want, but that sort of thing, and that's why the docs are important.

I watched the Kanye West doc on Netflix, and you’re in that studio too.

That you would have never seen the Kanye West behind the scenes or for even to me, I didn't know that that footage existed of us being in the studio at that time. It’s cool to look back. It's like looking back at college photos to realize that that time period is 25 years ago. Wow.

And it's not something where back then, to me, that was an average day. I did so much in that studio. I'm not gonna necessarily remember, but other people do, they're like, this was your Jay-Z time, and I'm like, ‘Well, for me, that was a regular Tuesday.’

I was just working on a project, and this happens, and that happens, so it's cool to like sort of look back, and as I said, it allows people to gain perspective on situations, you know, and still you have to take it with a grain of salt also to understand that it's his perspective, and nothing is right or wrong.

One of the big things was he didn't edit when he goes in the office, and he's playing this song, and people are just like ‘How can anybody in this office be in the music business and hear All Falls Down, and not automatically think it's a hit?’ Like Whoa, we've heard it ten times by that time. That's what you don't get. We've heard it already. Kanye plays it for you every step of the way.

One of the cool things was that one of the people in Clubhouse admitted that he stole my CD. He stole my Lauren Hill CD to go make All Falls Down.

Because I was a huge Lauryn Hill fan, still, and I had ‘Unplugged’ at that time. So it's all these little gaps that you don't know that you fill in, and this gives us a chance to explain our side of the story. Nobody's fronting on him, but if you're one of our top producers, not the top producer, we look at it as our main go-to. So if I'm working on a Beanie Segal project, and a Memphis Bleek project, and a Jay-Z project, and you walk in the door, I'm thinking of material for them. I don't think I'm insulting you when I say I want beats, and I don't want to listen to your Raps right now because I'm focused on these projects. When it's time to focus on your project, I'm not going to be focused on anything else either.

So it's perspective of someone's hunger, and they're like, ‘Oh, this person is not listening to me, or they look at me in this way.’ I went through that transferring from being a DJ to an Engineer because people knew me and knew me as a DJ. When I said I knew how to engineer, at first, I couldn't get mixes in New York. It was like, ‘Yeah, we'll let you record, but Elai Tubo was mixing everything, Tony Maserati, Joe Quinde, they were mixing everything, and it was because that Bad Boy people at the time knew me from Howard as a DJ. So when I say I know how to engineer, I know how to do it, it's like you got to kind of flip the thing of how you view me, you know I mean? It's not that somebody doesn't like you or isn't trying to give you a shot.

How did you prove yourself back then?

Chucky Thompson. He was my everything. God bless the dead man. Chucky Thompson was my breakthrough. He believed in me. He was the person who, as I said, was the executive producer of Nonchalant’s second album I started engineering.

But then he got to a point where he said I need to take you to New York with me. Back then, budgets were huge, so everything was paid for by the label. So if we're flying from DC to New York to work on a song, Chuckie would also put in the budget that he needed me for, and I'm saying first-class ticket. You're flying to New York, and then he's sitting me in a room with Tony Maserati when he's mixing a Bad Boy Record that Chucky produced and goes: ‘Yo, learn everything he knows.’ Chucky was my complete break I'm going to give you this opportunity to mix, record, and show what I know. He was my breakthrough, especially during that time period. And there was another thing, and Chuck was just a big enough person, I was like, ‘Hey, I feel stagnant in DC because there's not enough work for me there's more work in New York. If I just live in Jersey because my family's from there, then I can take a session because you're going to get a phone call at one in the afternoon like, ‘Hey, can you show up at five?’ Yes, okay, cool.

Because back then, record labels would have meetings in the morning, they might discuss a problem or something they wanted to change in a record or anything, and they may have an artist come in and recall things.

We're so used to it now when we sit at home, even after we've mixed in a big studio. People like, ‘Can you send me the stems of such’? And you're like, ‘Yeah, no problem’! We didn't have that back then, so if there's a recall to be done, and the labels wanted the drums need to be stronger, that's a total recall. That's another two thousand dollars. That's taking, telling the assistant to put all the equipment back the way it was, and he's sitting there with a physical piece of paper that you mark down from the mix, and there's an adjustment there.

So it was not as easy as today when somebody says, ‘Oh, can you just do a Vocal Up, and you're just hitting the fader on your stems up.

Without SurferEQ, I would have to be sitting there with a real EQ doing this and that, knowing exactly where it's going for the whole mix, which is impossible.

Let’s get a bit specific with mixing. Do you have a blueprint, and is there any method?

So before COVID, I never really liked templates. I would say, ‘How do you do a template because every song is different.’ Meaning I had to learn the difference between presets and templates, and I was thinking of a template as a preset like you just have these plugins set up ready to go, and then you just do the same thing, and I was like, No, No No. Now I use a template that I have for mixing. When I get whatever session, I’ll listen to it the way they have it. But then, that's what I do here at home, I listen and figure out what problems are there, simple problems that I can figure out.

For example, did this person edit on the grid, and there's a clip every time it goes over because it doesn't perfectly end at that thing? So you got to kind of fix the clips, fix things that are not sonic choices. Things that are like cleaning, like taking background noise out or having to gate less. Because you can sit there and just chop out the audio during the times when there's not supposed to be anything. All of those little technical things that are not, as I said, not audio choices, but things to clean up a session. Think of clip gaining so that you even start at the proper level.

Because someone gave you a vocal that's just sitting super high, and if I even begin to put this inside of plugins, it's going to be too loud. Because most plugins are designed for -18, as we hopefully all know. So now I do use a template, and it sped my work up.

When I was doing my Reuben Vincent project, even the A&R was like, ‘Man, Guru is knocking this out.’ And it was just two or three a day, because I have a setup, and I know the song, I've already listened to it at home. It speeds me up a lot faster. It became a combination of things that I always used to stay away from because the more simple the session, for me, it was better.

I wasn't this person who did a lot of parallel processing, I really sent a bunch of stuff to Aux, and it was like as if I had a reel, and just my Master is one and two, and everything happens inside of this.

I completely changed the way I work, one because of Stuart White, who's Beyoncé's Engineer.

We have to share the same space obviously, share the same computer. We have to have sort of this thing together where we know what plug-ins are on this computer. And a lot of times, he's giving me a session, and I look at it like this is the most complicated thing on earth. But it's his way of working fast, so when he's working with Beyoncé, and she asks for something, he doesn't have to go by a new audio track. Everything is all set up already from A to Z so that he's not fumbling.

He utilizes every feature of Pro Tools, and then I understood why he does that. So I started to incorporate a lot of the things into my mixes.

Or probably the most famous Mix with the Masters, at least for Urban Music, is the Jason Joshua one. You know everybody sits down and watches that thing, and it's not just to sit down and take the plugins that he's doing, but the way he's routing.

I never used to do ‘These drums go to the drum bus,’ and then I'm going to affect that, and do parallel processing on that, and then all that goes to another bus, and that's all drums. And then there's the main music.

But underneath the main music, there's this sample one, sample two, horns, guitars, and I'm affecting each of those, and then all of that goes to main music, etc. Am I separating the 808 into the bass, or is that part of the drums? Then I have a bass, and that all goes to all bass. I took a Sunday and just set it up the way that I wanted it.

And then going back and looking at old Pensado stuff and being like, ‘Okay, if I want to set up, let’s say 15 different parallel things for drums that all have a different sound, I'm watching every single person.

For example, watching Jason's thing got me back into the MV2 plugin. Then I'm also one of those people that love the Universal Audio, the 2500, that's perfect for ‘New York style’ bus compression.

It's not that I'm using all of them in my template, all the plugins are disabled, and I literally just go to my template, and I pull in every single track, and then it's in that session. Then I just apply the things that I need and the things that I don't need, then I can either erase them, or they just stay as tracks that aren't enabled. They're just disabled tracks.

And it's a much faster workflow for me. I'm still not big on the color coding thing, so I only have the color just on the sides because I don't like it being across the whole channel - visually, that throws me off. I used to hate color coding, but now I understand it, and in just my mind trying to take these things into account. Then I figured out, ‘Oh, you can just have it on the side and not across the whole thing, so that works better. I started learning things because I never would use colors. I hated the colors.

I’m saying all that, now I do have a template, and that's the way that I work, and it's made me much, much faster, and you can just develop certain things so that you don't fall into a rut of doing the same thing over and over again. But I do have certain things that became my workhorses. The waves F6 EQ used to be just my utility belt for EQs, and now it's the Pro-Q3. There's so much that you can do with that Pro-Q3.

And Surfer EQ is like, Jesus Christ, how come I didn't have this for bass lines like in the regular analog world?

We've all run into that where it's not a volume thing. It's just this note is louder and resonates more than this other note. And with SurferEQ, I can have it follow the note. I can not only have it follow the note, but I can dial in some harmonics.

Those sort of things have sped me up just tremendously in terms of not having to have 80 million plug-ins to be able to get that effect of this ‘one note’ is not about how hard. It's just the way the person played it lower than the other one. So now I have an automated way.

Without SurferEQ, I would have to be sitting there with a real EQ doing this and that, knowing exactly where it's going for the whole mix, which is impossible.

Let’s talk about mixes you utilized our plug-ins on.

Earl Sweatshirt. He's one that I used a lot of your guys' stuff on.

I did that project in my apartment before I went into a big studio, but in the end, I did the same process of doing everything at home and sort of going to test and do final finals like in a big studio. And it just translated so well from me learning this room because that was a big thing for me.

Obviously, I'm really big on SurferEQ, and obviously, you're not going to get the same bass in this home environment. And I purposely don't have a sub in my home studio, just because I wanted to hear exactly what it sounds like. Versus with subs, sometimes I’m guessing as to where it should be set because you don't want to overdo it you don't want to underdo it. I think SurferEQ just saves me so much on the bass and adding that harmonic without having to go to a different plug-in and having various harmonics that you can add really helps.

I think that's one of the biggest things you guys have done with that SurferEQ.

Being able to add the harmonics and just the ability to follow the root note that means so much.

People do not understand that a root note, any note is not stagnant, so when someone's playing there, you know the root note is moving. We know the root note of the key, but where the bottom frequency is of whatever note you're playing, it's moving as you're moving notes.

So if you're EQing with a static EQ, it's like you're hitting certain spots, and at certain times it's not in that space, depending on how big the Q is of the EQ that you need. So having a smaller Q because I only want to affect these particular frequencies but have it do this 'Surfing' is just immaculate.

Last time we spoke, you mentioned that POWAIR became a tool that you utilize a lot.

Because it's not just a compressor, it's not just a limiter. It works differently.

I think it's properly named, and I had to get into it to learn it because it's another sort of utility knife that allows you to do anything. The best way for me to kind of describe it is when I first got a distressor I only used it in one way, and then I sat down and read the manual. And I was like, ‘Oh,’ this is every compressor. This is the LA-2A. This is the 1176. POWAIR is an aggressive thing for my kicks and snares! That's what happened to me with POWAIR.

It was like I got it, and I looked at it as one thing, and then I read it, and I’m like ‘Oh’ this can do a lot! That's when I got into utilizing POWAIR and looking for just different things to use it for in my normal everyday.

How else are you creatively involved?

It depends on whatever the thing is. I do Djing to the public, not in just one style. I like to do all styles. Some people only do the posh, like I'm getting paid this much, ‘I'm a celebrity DJ,’ and they do Movida in London or something like that. I've done Movida a bunch of times. Or they won't do the Underground because they're only getting a thousand dollars for this set, and they're a 'Celebrity DJ,' which gets 10. And for me, No, I want to do that too, just to be able to be In Tune with what's going on in that time. Or someone who's like, ‘I only play Afrobeat. I don't play the new young stuff.’

For me, it is whatever the crowd wants.

And I want to figure out crowds and how to move people, whether or not that's in Dubai, in Africa, in India, in London, or in the United States. I was proud of, before COVID, I finally cracked South America. I had never played in Colombia, so I finally got a chance to play in Bogota and Medellín and all these other places. It's a new crowd, and I gotta see what they like.

Jeymes Samuel just put out ‘The Harder They Fall’, which was Jay-Z’s first sort of introduction to his Movie House. And Jeymes is a good friend of ours, an incredible director, but also a musician. When we were doing not only the songs that Jay-Z appears on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hppl5BnFH1Y but doing the movie, there's discussion.

I don't want to say I was the musical director, but I'm sitting with the Director of the Film who happens to be my friend, who I have a lot of music discussions with, and life discussions with, and obviously if he's working on that project, we're having a lot of discussions back and forth about the music that goes in.

So our discussions were about sort of changing the under-bed of what is normally done in a Western. The idea of what Jeymes said to me was, ‘Guru, think of The Spaghetti Westerns Music and the top layers of the Spanish Guitars, the whistling, that sort of thing. But I want the bottom end to be Raggae, I want the bottom end to be Reggae Basslines, and because in Jamaican culture, people love Westerns, because Jamaicans love gunfights. It’s a thing of sonically going to think of sound clashes, think of that you know someone against someone, and what the reggae feel of that. And those bass lines work. So the whole idea was taking those bass lines or putting the top part of what we normally have for Westerns and knowing what that is, and just knowing how to develop the idea. Yes, I’m technically engineering on songs. Jay-Z did two songs for the movie. There's another song that was really big that I thought was just incredible, and it goes to Jeymes’s sort of genius. Sometimes it's not just what you do, it's what you don't do. It's like making decisions to exclude certain things.

I have this great song that we paid for, and we got the rights to, but when I'm sitting down looking at the final movie, it just doesn't fit that scene because it's too slow, and the scene goes fast, and I need to set this up for my characters. But I love the song, and I'm attached, so it's those decisions as a Curator of going ‘This song is so good, but it would slow down the pace of this scene, and you have to make those decisions, too.

That's creatively kind of what extends beyond just like recording and mixing for those sort of projects.

Ron Bartlett, Oscar-winning Dialogue Editor, used Auto-Align Post 2 in The Harder They Fall.

That's another part of it too. It's interesting to watch someone who kind of does what I do, but in the video sense, so I'm watching the video editor and how he's working and what those technical things are that he's doing. How his sessions look and then obviously audio-wise what they were doing.

It was just really interesting to watch something where you, being an Audio Engineer, understand exactly what he's doing. You're looking at his program. You know what program that is, and I learn to understand what is that, how that works, and how many tracks you get. What can you do? What plugins that come from our world are working there? You start asking all those questions.

Do I know everything he's doing with video? No.

Do I know what formats he has to give it in? No.

Do I know how certain technical things work? No.

But it’s fun to sit there and watch someone else work and just sort of pick up those things.

The same way other people know a little bit about Pro Tools and a little bit about Ableton and some of my artists don't want to know the deep dive. They just want to go set it up so that they can hit the Command and the Spacebar and record themselves. That's all they need to know, after that they give it to me. But when their at home, they want to know how not to distort, so they can just knock these ideas out. I think it's that thing in the worst with me with video.

Where do you think the music industry is heading with AI and machine learning?

I think it's going to get to a point where AI is going to be good enough that the common person can start to say something like ‘I want to do this or that,’ and verbally just say it to the computer, and it's going to be able to do that.

Now, no matter what, you're always going have to have human input, and the reason that I say that, and people can argue with me on this, and we've had years and years and years of scientific discussion about AI, not just for music but just in general what does that mean.

Because you still have to feed in information. It's not making a decision. You're just feeding information.

You have to realize where we are in the music business and that a lot of the things that were done before are automatable.

If I take the history of music and I feed it and analyze it, which many people are doing, right? Like at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), there was a project years ago where they would try to take all of the history of Jazz and feed it into a Computer so that the AI could then go, ‘Okay, write a thing in a John Coltrane style. And it’s still writing in a John Coltrane style.

And they’re going to do, ‘Now I want a composition that is 40 percent John Coltrane style, and 30 percent Thelonious Monk and 30 percent Art Blakey’, and you're going to try to figure out what does that mean. All it’s doing is looking at how many times you went from this F to this G and then went back down here and what's this, and it's still only regurgitating what you gave it.

Meaning, when we as humans do that, there's a part of when we're learning someone else, and learning what they did, and we play it over, there is a part of it that makes us do it differently and make us do it our way. That's the part of the inspiration of the human being that the computer will never have. It's gonna be good, it's gonna be fast, and it's gonna be enough for…let’s say Avatars, right? People are getting into this world where they're gonna create an Avatar, and in the Metaverse, you create an Avatar who's going to become an artist, and you're sitting there, and you're almost like in Guitar Hero, pressing a button that spits out a song to you. And then, do you like this? ‘Well, I like the drums,’ ‘Okay’we'll change the bass line, and you want the bass line different, and you're just tapping a button on it. It’s almost like producing in Guitar Hero, right? You don’t know how to play it. It's going to feed you back options, but I've had to feed that many MIDI files for it to flip to something else, and flip to something else, and flip to something else.

That's where I see we're going with AI, but it's going to make it so that the human interaction in terms of sparking new things always has to be there.

It's not to say that like if you send a master to LANDR. They have gotten a million times better with feeding in algorithms and giving you a master back. However, it still does not compare to me giving my music to Tony Dawsey and having a conversation with him, and him doing a mix and going, ‘Okay, let me print this onto a CD and ride around in the car and come back. And then I'm like, ‘Okay, well, do you want the one that's compressed, or do you want the uncompressed?

Because you're running it through your shadow hills, and I don't want to give it to you too loud - this type of conversation is not going on with the Computer.

Yes, AI speeds things up, but I'm never scared of it in terms of like losing my job. That's the big thing.

But have to realize where we are in the music business and that a lot of the things that were done before are automatable.

Follow Young Guru

https://www.instagram.com/youngguru763/