Do It For Your Own Passion

Combining a classical background with a love of electronic music and tech.

Tom Player

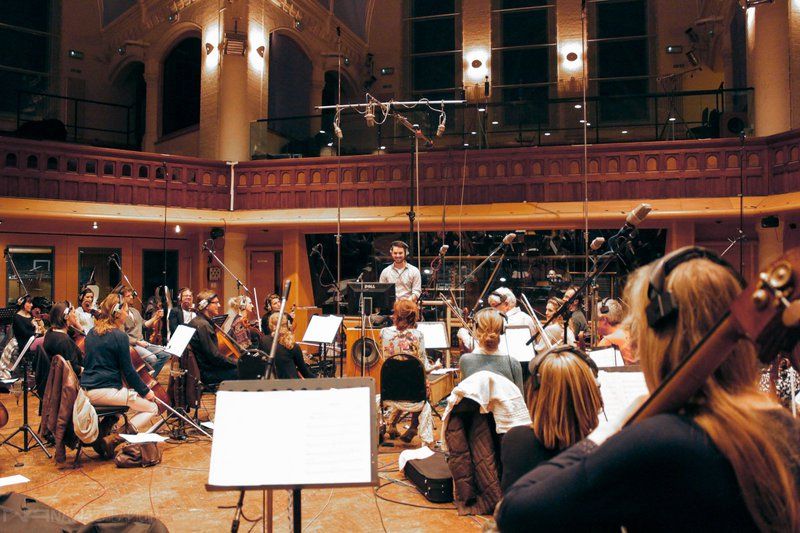

Tom Player is a British composer working on high-profile adverts and film trailers (The Hobbit, Game of Thrones, Ikea, The Sunday Times), composing full orchestral albums, and assisting award-winning Hollywood composers including Hans Zimmer and Ramin Djawadi. Combining a classical background with a love of electronic music and tech, he is a fascinating talent to talk to. He tells us how the discovery of Sound Radix has revolutionized his work.

My musical background comes from playing the cello. I have a musical family, and my mom is a multi-instrumentalist. As a rebellious kid, you naturally choose the cello because it’s the instrument your mom doesn’t teach! So I’ve been learning and playing the cello since I was very young, and I had an interest in electronic music and DJ-ing and producing. I think my first ever dabble in electronic music was with a computer program called Pro DJ, which was basically like a really early version of Ableton Live, where you just drag loops in and arrange stuff.

Then I went into FruityLoops, Cubase. You kind of learn everything along the way.

I’ve got a classical music background, playing the cello in orchestras and performances and things like that. I decided to take it a bit more seriously when I went to university. I was at the University of Surrey, which is famed for their ‘Tonmeister’ course. I was on the first year of a brand new course called Music and Computer Sound Design (which I think has now changed to Music Technology). There were a bunch of really great lecturers and really interesting courses. And that basically gave me the opportunity to explore different areas of music and music technology, experiment with things, and get a really great education on the theoretical aspects, as well as meeting loads of great people.

On the side, I was DJ-ing, producing, and hosting drum and bass events, because that was one of my favorite types of music at the time, and also played in an orchestra. So I had all these different sound worlds coming along. I’ve found having had this breadth of experience really helpful.

As you were growing up would you watch movies and listen to the score, thinking, hey, how did they do that?

Actually no! I think, in retrospect, I just enjoyed films, I don’t think I had a complete obsession with film scoring. It was only when I went to start assisting film composers that I appreciated how much work went into it and then looking back retrospectively at your favorite films you realize a lot of time it’s because the music is so good. There’s so much going on behind the scenes of these projects that you never really can appreciate them as a younger kid, but I definitely remember now my favorite pieces of music in my favorite films from back in the day - all the old John Williams and Alan Silvestri scores, and the early Bourne stuff [The Bourne Identity, scored by John Powell].

So when did the big break come when you ended up at Remote Control with Hans Zimmer?

I actually had my results in my hand on graduation day at university and got a call for a job I had previously applied for, which was with a guy called Richard Harvey, who is a very good composer. I went to work for him for a couple of years, doing lots of international film projects and library albums and things like that. He had two studios, one in London and one out in Thailand. Every year I would go out and assist him in London, and then he’d occasionally fly me out to set up his studio in Thailand as well. One year he said, ‘so everything’s set up and running really well, so why don’t you go and work for a mate of mine?’ I had no idea who it was, but I said ok, sounds good, I’m up for meeting new people and exploring. So he said you need to go to L. A. for a couple of months and I was like ‘ok, that sounds exciting…’ Then I found out later this guy was Hans Zimmer! It was all very played down on Richard’s part, but I was very excited! So I flew out and assisted Hans.

It’s a completely different world out there. The pace and the workflow is incredible, all these guys work so so fast because they have to. There’s sometimes only a matter of several weeks to get an entire film project scored, approved, and recorded. It was a great learning experience to see how those guys worked and how fast everything came together.

Talking about your development, it’s clear you are comfortable both around the classical and more modern genres, which must involve good tech. How important has tech been in your career so far?

It’s completely essential! The idea that if there was a power cut tomorrow, I could sit down with a pen and paper and write out a piece of orchestral music is daunting - it would easily take me 10 to 15 times as long. Tech is an enabler; it makes everything so much easier, so much more instantaneous. I think to be a modern-day composer you can’t do it without technology.

What’s your workflow in particular, how do you approach a piece of music?

It’s changed over the years, but what I’m doing at the moment seems to be the best way I’ve found of coming up with strong compositions. I try and make everything work on a piano. I’ll have 5 or 6 different piano tracks, each one representing a different role in the orchestra - so one could be the strings, one could be the woods or the brass. Writing a piece using basic sounds - piano sound with no expression - really forces you to use your imagination. One of the drawbacks of technology is you don’t necessarily have to imagine; because the samples are good, you don’t have to imagine what it would sound like. So doing everything on piano, making sure it works as a composition, and then fleshing it out onto an orchestra is the way I’ve found works for best for me.

What do you use most in terms of technology? Are you still using hardware of any kind?

I’m trying to cut out as much hardware as possible really, because although I’m sure it sounds brilliant and it’s fun, there are several reasons I prefer not to. One is because it slows everything down; you have to recall everything, and patch everything together. Two is that if you have an amazing Pultec or a Massive Passive EQ, I’m sure it sounds great, but the way I work is I don’t like to commit to things in the mix until the last minute. So I’ll use 15, 20, 50 EQs and compressors, all sorts of things running at the same time, so that I can go back and tweak something if I need to. The idea of EQ-ing something early on is not great. Also it would be so expensive to own all those units; it becomes a nightmare to patch in and out and very expensive to run. So emulations are really helpful and I just I run as much off my computer as possible. The key for me is to make sure it sounds as good as possible at source. Which is why I go to lots of studios in London to record stuff, and to try not to fiddle with it too much unless it’s really necessary.

Do you find it difficult handing your work over to the final mix guys for it to go into a big mix as part of a film score? Do you ever listen to a movie later and think ‘that’s not quite how I had it in my head’?

Yeah, that happens… The most difficult part is handing things over in stems. Which obviously gives flexibility to the dubbing engineers, but also gives a massive opportunity for them to mess it up! I did a World Cup ad for Vauxhall which was a synth and rock version of Elgar’s Nimrod, which is obviously an incredible piece, revered and respected, but they wanted to make it sound more modern. So I did that, and the dubbing place in Manchester asked for 9 stems. Everything had been signed off by the head of brand and the ad agency; everyone was happy. It was sent off just get vocals and sound effects added to it, then it came back and we got some really weird feedback - they were like ‘Erm, ok so it sounds a bit sort of old fashioned and traditional…’. We asked them to send what they had heard, and what had happened is the sound engineer had decided to mute 7 of the 9 stems – all the synth stuff! All you had was this lame flat sounding orchestra. They had no excuse, it was a disaster! It all got sorted in the end and everyone was happy – it won some awards in fact – but that was a brilliant example where it’s good not to give stems!

I once worked with a composer who asked me is there a way of giving people stems where they can only turn it up? That would be a great invention, maybe that’s the next plug-in!

What is it that Sound Radix brings to your work?

The thing I like most about Sound Radix is you’re not trying to model plug-ins on things that exist. What you’re doing is thinking outside the box, thinking about what do people want, what is the end result that people want to get. What are the drawbacks of technology at the moment, and how can we remedy that?

I found the Sound Radix Auto-Align to be completely indispensable on a project I’ve just done. When you work with lots of multi-mic set-ups and mix a lot of the stuff yourself, you don’t necessarily realise how phase cancellations and comb filtering can be affecting your final mix. Sometimes you’ll listen to it and it sounds cool but a bit weird, then you put Auto-Align on it and it saves you dozens and dozens of EQ moves, and everything just sounds right, it sounds as you heard it in the room.

I was looking for a simple phase alignment plug-in on the internet and I found Auto-Align. I’m usually a bit more hands-on than the name would suggest, but I gave it a go. And it had such a profound effect on the album. I basically had to re-mix the entire album with Auto-Align on nearly every single multi-mic track. It was a breath of fresh air, I felt like it was an amazing thing. After that I went back and looked at every single plug-in that Sound Radix had. I found Drum Leveler, which is another plug which saves me a remarkable amount of time on volume automation. I’d say it is probably the most transparent way to make performances consistent. It’s not really a compressor in a sort of traditional sense, it’s actually a really intelligent volume leveller, which you can run into a compressor if you want to get that sort of tone. If I’d had Drum Leveler on my last big orchestral album Resonance Theory it would have saved me weeks. Without it I had to go over every single stem, and volume-level nearly every single staccato or every single rhythmic hit that was recorded - with live players you always get a little variation between each hit. You want to make it sound consistent but you don’t want to have to compress the hell out of it. So I was automating each level and then running it into a compressor. With Drum Leveler, I think I could probably have saved myself weeks of time of automating with a tiny little scissor tool and Cubase or Pro Tools or whatever I used. So it’s really really useful!

That’s interesting that you decided to use something called Drum Leveler on orchestral music!

I thought calling it Drum Leveler was interesting…it makes it seem like a specific tool. What is does for drums works great, but if you have a certain type of rhythmic effect it’s going to work just the same on anything else. As soon as you understand how it works - basically an envelope-triggered levelling system - then you can use it on almost everything. I was using it on upright bass, I was using it on rhythmic string writing… I was using it on pretty much everything apart from drums really! It’s nice to breathe new life into a product that it’s not necessarily designed for.

You said you’d had some reticence at first about using Auto-Align. But that’s become a big part of your work flow?

Yeah basically I’m quite a hands-on guy and I don’t really like things that try and take control away from what I’m doing, because I like to think that every decision I make I’ve come to with a matter of deliberation. So anything with ‘auto’ in it kind of makes me cringe! But the amazing thing about Auto-Align is it doesn’t just give you the correct phase, it also gives you the opportunity to try different phase points. It allows you to try different super-positions of the phase - where the waves hit each other - to give slightly different colouring to the sound, and these are things that you’d never do if you were just trying to line up the samples. So it actually does a much better job of lining up the phase than your ears would, or even if you use the clicker on the mics. So it’s like a superman little plug-in, it’s amazing. For something that does so little, it does it so intelligently that it deserves a better name than Auto-Align really!

As a young guy you’ve already made a really good name for yourself in the industry. If you could give one piece of advice to other aspiring composers what would that be?

I would say that probably the most important thing to remember is to enjoy it, and to make sure you’re doing it for your own passion rather than anything else. I hear stories of composers trying to churn out five library tracks a day, and that’s my idea of hell - how to take something you once enjoyed and turn it into a job. Try and have fun with it; if you’re good at it, and you’re really passionate and you really care that’s what people see in you and that’s what draws the success. If you go chasing money or what other people think you should be doing, you’re probably not going to be the best composer that you could be. Also don’t have too much of a plan, because there are so many opportunities for music out there that if you shut too many doors before you’ve tried everything, you might never find the thing that really appeals to you. I had no idea that I would be doing what I’m doing now, full-time in a nice studio in London… I’m really fortunate to be in this position, and it’s pretty much because I’ve been quite flexible and willing to try different things and experiment, and try to put out the best music I can.